In part 1, our group began to explore Tuibun Village. We felt privileged to visit the site and to learn about the Tuibun Ohlone. The Tuibun were one of the Native Californian inhabitants of the San Francisco Bay Area.

The 2,000-year-old village site lies in a freshwater marsh that borders San Francisco Bay. I had always wondered about the skills people used to thrive in a marsh environment. In part 1, we enter a replica shelter made from tule reeds (Schoenoplectus acutus) and then hike to the archaeological site. We spend time in a replica sweathouse learning about its use.

Volunteers from the community and park staff built several replica structures at the village site. Our guide, Dino, explains that they constructed them away from where ancient structures actually stood. As we continue our walk, Dino interprets the cultural history of the place.

The Pit House

We enter a large subterranean structure that would have housed a leading family. We enter through the side of this replica. But the entrance to many subterranean homes was a ladder through the chimney-hole in the roof.

We enter the pit house

The pit house is a large structure that easily accommodates our entire group.

The inhabitants stored personal belonging in baskets hung from the rafters. Like sweathouses, soil covered the roofs of pit houses. This replica house had a redwood bark roof.

It was dark inside. But the vaulted ceiling and large entrance lend an airy feel to the cool, dry interior. We find seats on log sections distributed around the perimeter. Once settled, Dino begins to tell stories about what life might have been like in the village.

Pit house interior.

The central feature is a fire ring in the center of the circular house. A hole in the roof permits smoke from the fire to escape. The fire primarily warmed the shelter. Cooking was done outside.

Most daily life happened outside the shelter. The house was mainly for sleeping and storage.

Dino conveyed a picture of what it would be like to live in this house 2,000 years ago. Scientists believe that residents of the time lived into their 40’s, on average.

Dino tells stories of life long ago

The Tule Mat

The homeowners slept on insulating mats made of tule from the nearby marsh. Dino had a small sample so we could observe its construction. In the sample sleeping mat, the tule reeds are woven with cotton cords. The ends of the cords are tied to a length of plant-fiber cordage that runs the width of the mat along one border. I also notice that the ends of the tule are folded into the mat for a more finished appearance.

Tule sleeping mat. Cotton thread is twined around tule reeds.

In this example, the cotton cordage is tied to natural fiber cordage that runs the width of the mat.

I searched online and found instructions for making a tule mat. If you have made cordage using the reverse-twist method, the instructions will look familiar:

To twine tules into mats or other items, begin as you would for rope, twisting together three or four inches of single ply cord. Instead of twisting the plys together, place the twisted section around a small bunch of tules with each twist. You should have the tules laid out roughly.

Pass the strand which lies on top of the first bunch over the strand which comes up from beneath, and then this strand passes beneath the second bunch of tules and then comes back out to the working face. Repeat this – over, behind and out – until you have completed a row. Add in additional pieces of cordage as needed to maintain the thickness of the strand.

As the row progresses, each ‘stitch’ should slant at the same angle across the face of the project. At the end of a row, twine the cords into rope until it is long enough to reach the next spot you want a row to begin, then turn and twine the row. Continue this process until you have finished. End the last row with a knot, then tuck the ends back into the work.1

Rabbit Skin Blanket

To keep warm, the house’s occupants would have slept underneath rabbit skin blankets. Dino had a small sample for us to examine.

Dino describes how to fashion a rabbit skin blanket

The sample blanket was made by twining cotton cord through parallel strips of rabbit skin. The middle of the cord was tied to an end strip and the two lengths were twined through the middle strips. Each twist of the cordage held fast several strips.

As the blanket circulates among the group I am able to examine it in detail. It is extremely light and soft. It feels luxurious to the touch.

The rabbit skin blanket

Knowing how it was constructed, I probed with my finger to find a gap between strips where it was twined. When my finger appeared through a gap, the young woman sitting beside me worried that I “broke” the blanket.

Strips of rabbit skin are twined between cordage. I poke my finger through a gap between strips.

Here are instructions for how to make a rabbit skin blanket. They are consistent with the method Dino described. It is an involved process that requires many rabbit skins.

As I caress the plush fur, I imagine the pleasant warmth of sleeping under a full size rabbit skin blanket.

Tule Saw

Next, Dino produces a small saw fashioned from a deer scapula. He describes how it’s used to cut tule. As he passes it around the room, Dino mentions that he used his replica saw to collect tule, and that the wear patterns match saws found in the archaeological record. I am delighted! I have a weakness for experimental archaeology.

Dino discusses tule harvesting

This tule saw is made from a deer scapula.

The Rest of the Village

Finally, we exit the pit house to tour the rest of the village.

Pit house interior

The replica houses are away from where the original structures stood. This helps preserve the site. The rich dark soil is full of organic matter and the detritus of ancient habitation. Shards of stone and seashells appear wherever the soil beneath the surface is exposed. The photo below shows a cross section of soil photographed outside the entrance to the pit house.

A place where the soil is exposed shows signs of ancient human habitation

Our Final Place

On our way out of the site, we pass a “shade house.” I notice I am sweating from being in the hot sun. And it occurs to me that the original residents must have faced similar conditions. The shade house is a clever device that provides shade to people working outside. Its wood framework is lashed together and topped by a roof of green branches.

Shade house

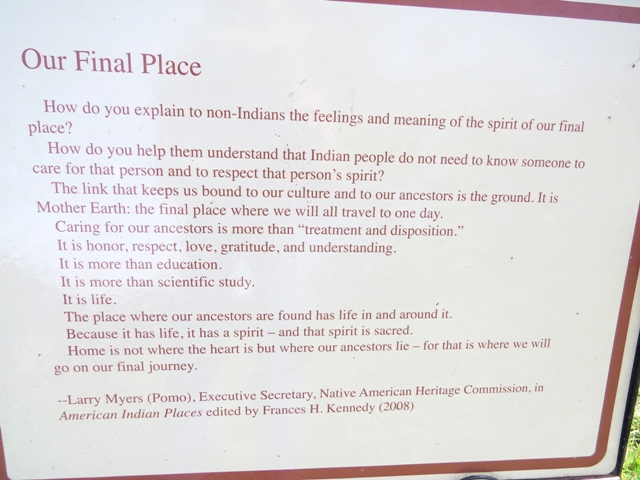

I will end this post with a photograph of the interpretive sign that stands in front of the shade house. It reminds us to respect this site and all others we may visit in our travels:

Always respect ancient sites

Notes

Related Articles on NatureOutside

The Tuibun of Coyote Hills (Part 1)

Archaeology, Technology, and Native Peoples

If you liked this post, you may enjoy others in the Trips Section.

Leave a Comment