It’s early morning and I’m at Rancho Canada del Oro, in the foothills of the southern Santa Cruz Mountains. The cloudless sky promises a hot June day.

I gaze upward at the hills towering above me. They’re covered in the golden grassland that gave California its “Golden State” nickname. Clumps of giant oaks rise like outdoor sculpture above the swaying grass.

My plan is to hike about 5 miles, gaining almost 900 feet of elevation. And I’m eager to set out as soon as possible to minimize my time in the scorching sun.

I’m after exercise. And as I heft my backpack, I gaze downward disapprovingly at my protruding stomach. I don’t need a scale to tell me I’ve gained the “COVID 19” while working from home. Shaking my head ruefully, I set out on the trail.

Looking down from a hillside in Rancho Canada del Oro.

Truth-or-Deer.

A few minutes into the hike the trail wends between two clumps of large oak trees. As I’m walking, movement in the shade catches my attention. I sense more than see the animals feeding under cover of the trees.

I’m glaringly exposed in the sun, on the edge of the trees. So I slowly “fox walk” into the nearest shade. I take slow steps, about half the length of my normal gate. Any time I sense movement, I freeze. As I move, my right hand reaches for my camera, held to the shoulder strap of my pack with a spring-loaded clip.

When my eyes adjust, I see at least two families of Columbian Black-tailed Deer foraging underneath the oaks. Among them are several fawns, still with their spots!

This fawn still has its spots. It’s little more than two months old.

Mother keeps the fawn close by her side. The bright leaves are the sweet smelling California Bay Laurel (Umbellularia californica).

I’m always excited to see fawns. Both the rarity and the “cute factor” make it a thrilling experience.

These fawns would have been born two months ago. And it will be another two months before they lose their spots. It’s difficult to tell from my pictures, but the spots provide excellent camouflage against the fallen oak leaves.

As I remain motionless observing the deer, I hear movement behind me. I recognize the rhythm of the gait and the weight of the footfalls. Another family of deer are passing behind me. They don’t notice my motionless form, clothed in earth-tones and crouched behind my camera.

Among the second group are several yearlings, deer born the previous summer. The males have spikes, still in velvet. I guess these bucks are about ten or eleven months old.

This yearling was born last summer. His antlers are surrounded by skin rich in blood vessels (velvet).

The antlers will continue to grow. Eventually, the velvet dries and flakes off.

When a buck is born, he has two swirls of hair on his forehead that show where antlers will develop later. They grow from pedicles, the cells on the front of the buck’s skull plate that anchor the antlers. At two or three months of age, the cells above the pedicles form bony knobs. By about six months of age, the pedicles are about ¾ inch long. A deer at this age is known as a “button buck” because of the raised bumps on its head. At ten months, the buck grows his first set of antlers. This is what I was seeing here.

The antlers are covered in “velvet.” Velvet is modified skin composed of tough collagen fibers. The tissue underneath is richly supplied with blood from special muscular arteries. The arteries can constrict to cut off the blood supply to prevent hemorrhaging if the antlers are damaged. The blood vessels deposit calcium, phosphorus, and magnesium on the growing antlers (antlers are bone). When the antlers are done growing, the velvet dries and flakes off.

Q: Why did the deer get braces?

A: He had buck teeth!

Deer and the Seasons

I’ve written before about how you can make a wild foods calendar and given you a template you can download. You can use the calendar to track when you should expect to see wild edibles in your area.

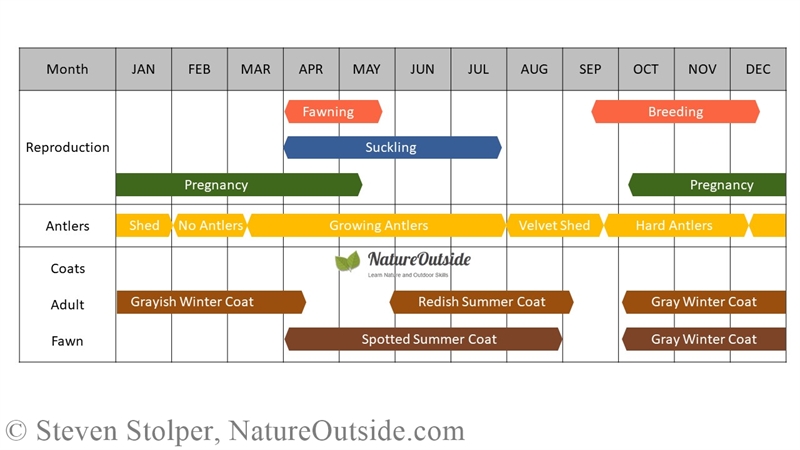

You can use the same approach to understand the life-cycle of deer in your area. Using your deer calendar, you can estimate the age of the deer you observe.

Deer have a well-understood annual cycle. If you know the cycle, you can create a deer calendar based on your observations. I created mine by first finding a scientific study of the deer life-cycle in my part of the country. Then I adjusted the findings based on my local observations. Here is my deer calendar:

I encourage you to make a deer calendar for your local area. It will help you understand the ages of the deer you are seeing and interpret their behavior. Use my deer calendar as the starting point for your own. Making one is easier than you think.

Q: Where do deer go for coffee?

A: Star-bucks!

Fawntasia

A few days later I stumble upon another family of deer, this time in a dense mixed-oak forest. It’s a doe with two fawns. The spots on their sides make it difficult to see the fawns when they remain still.

I found these fawns with their mother in dense forest in the Santa Cruz Mountains.

Notice how well the fawns blend into the forest when they’re still.

Family portrait.

Mother says ‘goodbye.’ These Black-tailed deer trot at around 10 MPH and can run as fast as 35 MPH.

I’m always excited to see fawns. And thanks to my calendar, I know when to expect them and can approximate their age.

If you’ve made a deer calendar, tell me about it in the comments below.

Related Articles on NatureOutside

Change Your Trail to Change Your Attitude

Hidden Houses – Do You Know What These Are?

For fun facts and useful tips, join the free Bushcraft Newsletter.

Leave a Comment