Viewing wildlife is invigorating – unless it’s a tick crawling up your arm! This post provides some basic information about ticks you are likely to encounter. There is a downloadable tick identification card at the bottom of this post for you to carry in your first-aid kit.

About ticks

Ticks are arachnids. They are more closely related to spiders than to insects. Like spiders, ticks have eight legs.

The two main types of ticks are Ixodid (“hard”) ticks and Argasid (“soft”) ticks. Where I reside in Northern California, hard ticks pose the greatest threat to humans. So the information in this post mainly deals with Ixodid ticks.

Ticks have three main stages in their life cycle. In the larval stage, ticks have only six legs. They require a blood meal and bite small animals including mice, rats, and birds. Tick larvae generally do not bite humans. In the nymph stage, they feed multiple times and may bite larger animals including people. Once the ticks become adults, they feed multiple times on larger animals that include deer and people.

It generally takes years for ticks to complete their life cycle. During their lifetimes, ticks cannot survive a season without acquiring at least one blood meal. Adult ticks die after laying their eggs.

It is a popular misconception that ticks “fall from trees”, “leap” or “fly” onto their hosts. Ticks do not have these abilities. Instead, they hunt for a blood meal using a behavior called “questing”. While questing, ticks hold onto leaves and grass by their third and fourth pair of legs. They hold the first pair of legs outstretched, waiting for a host to wander near. When a host brushes the spot where a tick is waiting, it quickly clambers aboard. Some ticks will bite immediately. Others seek places where the skin is thinner.

Ticks find their hosts by detecting breath and body odors, or by sensing body heat. They can detect moisture and vibration as well as recognize shadows. They are shrewd enough to wait in ambush along well-used paths.

Ticks and Disease

California has a relatively low rate of human illness due to ticks. Between 1996 and 2005, there were only 1,006 cases of Lyme Disease reported in Northern California (CPDH). This may be partially due to the Western Fence Lizard (see below). Other tick-transmitted disease are much more infrequent than Lyme Disease.

Here are the top three diseases in Northern California:

Lyme Disease

This is the most common tick-borne illness. In fact, Lyme Disease is the most common vector-borne illness in the United State (CDC). Between 80-100 cases are reported in California each year. It is caused by the Borrelia burgdorferi spirochete bacteria. The bacteria reside in the tick’s gut. When the tick ingests blood, the bacteria begin to reproduce and can migrate from the tick to its host in as little as 24 hours. In about 70% of the cases, the host develops a characteristic “bulls-eye” rash called an Erythema migrans rash. Lyme Disease is treatable with antibiotics.

Anaplasmosis

This disease is caused by the Anaplasma phagocytophilum bacteria. It is far less common than Lyme Disease. Less than 1% of ticks sampled in California are infected. This condition is treatable with antibiotics. Unlike Lyme Disease, it does not have an external rash.

Pacific Coast Tick Fever (364D)

Caused by Rickettsia bacteria, this disease is in the spotted fever group. Only 4% of ticks sampled in California carry the disease. People who contract the disease often show a dark crusted ulcer called an eschar. It looks very much like Anthrax and is sure to grab a doctor’s attention. This is a very severe disease and can cause grave illness. Be aware that horses and dogs are just as susceptible as humans.

Protect yourself from Ticks

The best protection from tick-borne illness is to avoid bites! Here are some tips for doing this:

Avoid areas that are infested. Where you find them is species dependent. I will discuss this further below.

Detecting ticks before they access your skin is important. Wear light colored clothing that makes it easier to detect them on your body. Wear a hat, long sleeved shirt, and long pants as a barrier to prevent access to your skin. Tucking your shirt into your pants, and your pants into your boots prevents them from slipping under your clothing undetected.

To actively discourage ticks from your body, use a repellent containing DEET or picaridin on areas of your skin not covered by clothing. Both chemicals have been shown to repel ticks. I have a natural reluctance to apply chemicals to my skin. So I tend to use them only when I know there is a high danger of ticks or mosquitoes.

I do, however, treat my hiking clothes with permethrin. Not only does permethrin repel ticks, but it is an insecticide that kills them on contact. I spray my clothing with a product called Sawyer Permethrin Premium Clothing Insect Repellent at the start of spring. When it is wet, it is hazardous to humans and should only be applied only in a well ventilated area. I wear long sleeves, long pants, and nitrile gloves when I spray. Once dry, the treated clothing is odorless and safe to wear. The treated clothing can be washed normally. But the agitation of the washing machine and the action of the detergents gradually remove the permethrin treatment. The product I use provides protection for 6 washes or 42 days, whichever comes first.

What to do if you find a tick

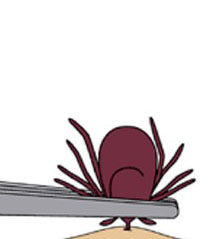

Grasp tick near mouth parts

Photo courtesy of CDC/PHIL

Although Lyme Disease requires 24 hours to infect a host. Many other diseases require far less time. For this reason, remove ticks as soon as you detected them.

When I arrive home after a hike in an infested area, I immediately shower and wash my clothing. This makes it more likely that I will find any hitchhikers. The shower can discourage a tick from clinging to my body.

I have never been bitten by a tick. So the directions for extraction come from the CDC, not personal experience:

- Place the tip of fine tweezers around the tick’s mouthparts

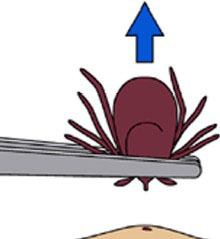

- Pull the tick firmly away from the skin. Do not jerk, crush, or puncture the tick.

- Do not use any of the “traditional” remedies. They do not work and can make the situation worse.

Gently remove tick

Photo courtesy of CDC/PHIL

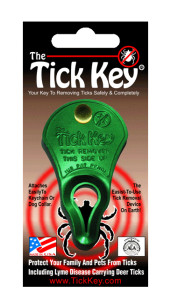

In my first-aid kits, I carry a “tick key”. This is a small device with a keyhole-shaped opening. You it drag across your skin and it lifts the tick away from your body. I have not tried it yet. But I carry it because it does not require the manual dexterity that tweezers do.

Wash your hands after you remove the tick. Treat the site with antiseptic. It is quite normal to have a local skin reaction to the saliva from the tick. This does not signify Lyme Disease.

Save the dead tick. Do this by wrapping it in a paper towel and putting it in a plastic bag. Place the bag in the refrigerator for safekeeping. If you become ill, the species can be identified to understand what diseases it may have carried. The tick itself is not tested for disease. If a person becomes ill, it is usually the patient’s blood that will be tested.

Know your Enemy

There are 47 species of ticks in California. But only 8 bite humans. Here are the top 3 (in terms of infection rates) in Northern California:

Western Black-legged Tick (Ixodes pacificus)

Look for adults between November and April. They inhabit Oak woodland, grassland, and chaparral. The nymphs are active March through July. Since they are prone to desiccation, they inhabit moist leaf litter, the moss on rocks and logs. Be aware that these ticks sometimes reside on picnic table benches (Yikes!). They carry Lyme Disease and anaplasmosis. See picture above.

Pacific Coast Tick (Dermacentor occidentalis)

These ticks are found January through May and like more open, sunny areas. They carry Pacific Coast Tick Fever (364D) and Tularemia. See picture below.

American Dog Tick (Dermacentor variabilis)

These ticks are found March through August. Like the Pacific Coast Tick, they like open sunny areas. They carry Pacific Coast Tick Fever (364D) and Tularemia. See picture below.

Lizards and Lyme Disease

For its size and population, California has an unusually low incidence of Lyme Disease. One reason may be due to the western fence lizard and the alligator lizard. Their blood contains a borreliacidal protein that kills the spirochetes in the guts of infected ticks. If an infected nymph Western Black-legged Tick bites a western fence lizard, it can be cured of its Lyme Disease. When it becomes an adult, it will no longer be infected.

It turns out that small lizards play an important role in the lives of Californians.

Download a Free Tick Identification Card

Here is a “business card” that you can keep in your first aid kit. It has life-sized photographs of the three most infectious tick species in California. Showing the different species is important because they carry different diseases. It also gives you the chance to go “tick watching”, if birding is too tame for you. 😀

The card also has a ruler printed on it and directions for removing attached ticks. Download the PDF file and print it out. Fold-over the two sides of the card and laminate it. Keep it in your first aid kit for future reference.

For More Information

Information contained in this post is from a conversation I had with Tina and Denise from the California Department of Public Health. Additional information is from materials published by the Center for Disease Control. For more information see:

California Department of Public Health Tick Page

Center for Disease Control Tick Web Page

American Dog Tick

Photo by Dr. Michael Dryden, College of Veterinary Medicine, Kansas State University

More Wilderness First Aid on NatureOutside

Wilderness First Aid and the Duty of Care to Yourself

Maxpedition Individual First Aid Pouch

Thanks for this post. I really appreciate the info and handy ID card and will refer to it often.

It’s surprising how little information is out there on identifying ticks. Do you have any info on identification of soft ticks? I didn’t even know that they existed before moving to Mendocino, CA and finding them on our dogs and cat regularly, year-round. I’ve found a few brief mentions and some species transmit Tickborne Relapsing Fever, yet I can’t find solid sources on proper identification. I will be sending one into a lab soon and will report back if interested! Thanks for all the info you provide on your website!

Jasmina

I’m glad you found the article helpful, Jasmina. It really is surprising how little information there is about identifying ticks.

UC Davis has a web-page about ticks commonly encountered in California. It has some information on soft ticks.

Hope that helps!

That’s a really great article Steven. I’ve seen the American Dog Tick around Lexington Reservoir and the Pacific Coast Tick along the Skyline To The Sea trail. Thanks for helping me identify them better. I like your idea of that key tool to remove them since that’s easier for me to see than with tweezers. Thanks again.

I’m glad you enjoyed the article, Sean. It’s cool you were able to identify the ticks you saw. I’ve been seeing ticks in the Santa Cruz Mountains near the Skyline to the Sea trail as well.

Great article on ticks Steve! Over 40 years ago I had Tularemia, probably from a tick bite. A scary few days and was cured with TWO penicillin shots!

This once-fatal disease is somewhat rare in Mississippi

Tommy

Wow, Tommy, I’m glad to hear that you’re alright. It’s a good thing it was correctly diagnosed. Tularemia is serious stuff.

Today I’m treating my spring/summer hiking clothes with Permethrin. Ticks-borne illness is no joke!

Ticks do not fly or leap, but they DO fall from trees. I don’t know how this misinformation spread. I am a biologist, environmental scientist and public health expert (38 years experience.) I have seen ticks perched on the edges of leaves above me and had them drop from trees both on me and in front of me. I agree they do not climb high in trees, but they do it.