If you never go out at night, you’re missing half the story. Many animals work the night shift. They’re crepuscular (active at dusk or dawn) or nocturnal (active at night). And the only way you’ll see them is to go outside when it’s dark.

When I traveled in Australia, I often hiked at night. I saw sugar gliders – strange marsupials that glide through the air like flying squirrels. I also spotted tree-dwelling animals completely alien to me. A vivid memory from that trip was a night hike through a temperate rain forest. I point my flashlight overhead and startle to see the shine of eyes staring down at me.

Whether it’s glow worms in New Zealand or leopards in Africa, I’m mesmerized by creatures of the night.

North America has its own denizens of the dark. Owls, opossum, armadillo, fireflies, and flying squirrel. Racoon, mountain lion, badger, and skunk. And of course, there’s bats…

Why Bats?

Bats are fascinating creatures. They are the only flying mammals. Others may glide, but only bats have powered flight.

In North America, our bats are primarily insectivores. A single ten-gram bat may eat several thousand insects a night1. They’re unsung heroes because they help keep humanity from being overrun with mosquitos.

Bats have an uncanny ability to fly at night. They echolocate, emitting powerful blasts of sound. In fact, their shrieks are deafening! Some bats generate 140 dB. That’s 20 dB louder than a rock concert and 15 dB above the human pain threshold2! Their sonic blasts echo off objects such as trees. The bats use the echoes to detect and avoid these objects in their path.

If bats are so loud, why don’t we hear them screaming in the night? The reason is that humans can’t hear them. Bats emit sound at frequencies between 10 – 120 Khz. The average human can’t hear anything above 15 Khz3. So, we occasionally hear bat calls. But most of the time their screams are beyond our perception.

My Chance to Learn about Bats

I had a chance recently to learn more about bats. The San Francisco Bay Bird Observatory held a “bat class” as a fundraiser. The class was led by Dave Johnston, Phd. Dave is a bat biologist and a vertebrate ecologist who specializes in the study of bats. He’s a well-known authority on bats of the west coast.

The class had three parts. Dave lectured about bats and his research on a Wednesday evening. Friday evening, the group went into the field to erect mist nets and radio tag any bats we catch. And Saturday morning, we’d search for their roosts using the radio transmitters we affixed the night before.

The lecture was fascinating. I learned that bats migrate. And that they face considerable danger from windfarms and human development. Dave often advises builders how to reduce the impact or mitigate the effects of their projects on bats.

What I took from the lecture is that loss of habitat due to urbanization is a major threat. Dave pointed out that 13 species of bats live in rural Marin County. But a few miles south, in San Francisco, there are only 4 species. So fewer species survive in our urban environments, especially among the tree dwelling bats.

Another threat is one you may have heard about. White Nose Syndrome has decimated bats on the East Coast of the United States. Mortality rates reach up to 100 percent at many sites! Bats transmit the disease to other bats. But the fungus that causes White Nose Syndrome is likely transported from cave to cave by humans on their gear and clothing. Unfortunately, White Nose Syndrome appeared in Washington State in 20154. That’s a jump of 3,000 miles from where the disease was first discovered. For those of us living in California, it’s not a matter of “if”, but “when” will the disease attack our bats.

Our Bat Expedition

The class meets shortly before sunset at a local nature preserve. We’re full of energy as we pull gear from our cars. We’re hoping to see Yuma myotis, big brown bats, and possibly Mexican free-tailed bats.

I’ve never had a chance to see bats up close, so I’m raring to go. But I won’t be handling any of the bats we catch. To participate in the actual tagging and banding, we need a rabies vaccination and a recent titer test result. I had not heard of a titer test before. It measures the level of antibodies to disease in a person’s blood. It gauges the strength of the body’s immune response. So, lacking these qualifications, I will not be able to handle the bats we catch.

Unloading the Gear

The mist nets hang on large metal poles. We unload the poles and select the mist nets we will use. Dave has different length nets, and we choose two for the night’s work: a 12-meter and an 18-meter net. We stretch each net and inspect the gauzy monofilament for holes. Then we roll the net carefully back into a plastic bag.

The nets have been sanitized in bleach. And they’re not entirely dry. Some of the color runs onto our hands and we’re careful not to stain our clothing.

While we’re preparing the nets, I’m pleasantly surprised to hear my name called. My friend, Barbara, is the naturalist for this preserve. We went through training together several years ago. I’m delighted to see her and we spend a few minutes catching up.

Dave unpacks the poles and nets. The nets are in the plastic bags.

We had metal poles of various lengths to choose from.

Stretching the Nets

We decide to set two nets across a nearby creek. Dave thinks the bats will enter the shallow ravine and fly down the length of the creek, eating insects. We bend the second net into an “L” shape. One leg of the “L” crosses a break in the trees that access a nearby meadow.

We stretch the nets among overhanging foliage. Dave says the “clutter” will help camouflage the netting. Remember, we’re not trying to hide the nets from sight. We want to disguise them from the bat’s echolocation. If we place the nets in an open area, the bats can detect and avoid them.

We run the nets just above the water’s surface, where we expect the bats to feed. But we’re careful to keep the bottom of the nets high enough so the bats aren’t immersed in the water if the nets sag.

We stake the poles as if they are volleyball nets. We use nearby rocks, branches, and even the concrete of a culvert to anchor the ropes. I tie a variant of the taut line hitch so we can adjust tension on the poles.

We secure the nets to the poles using a knot I’ve never seen before. It acts like a prusik knot. We can slide the knots up and down the pole and they still keep tension on the netting.

After we set up the nets, we slide the knots together so the net is not deployed. We don’t want to accidentally catch birds, or worse – deer!

Dave and a student attach the monofilament netting to a pole.

Dave unspools the netting as he crosses the creek

We attach the netting to the poles using a knot that is new to me. We slide the knots together to stow the net. This is a “safe” configuration when we are not monitoring the net.

We string the second net across the creek and then downstream

We need to check that the lines do not cross between each of the poles.

Walking the net downstream

Nightfall

As darkness falls, trouble is brewing. All week temperatures have been unseasonably hot. But in the last 24 hours temperatures have plummeted. Dave worries aloud that the bats will not venture out in these conditions. They’ll huddle for warmth and hope the cold spell passes.

I glance up at a streetlight in the parking lot. I expect to see a cloud of insects buzzing around the light. The solitary bulb beams back at me. Nothing is flying tonight.

Base Camp

Some of the links below are affiliate links.

Our base camp is far enough from the nets that we don’t disturb the bats. We lay out everything we’ll need on a picnic table: Nitrile gloves, paper bags (for the bats), measuring equipment, adhesives, transmitters, and banding equipment.

laptop computer for recording data, paper bags, measuring equipment, and a bat detector

Our supplies are ready to go

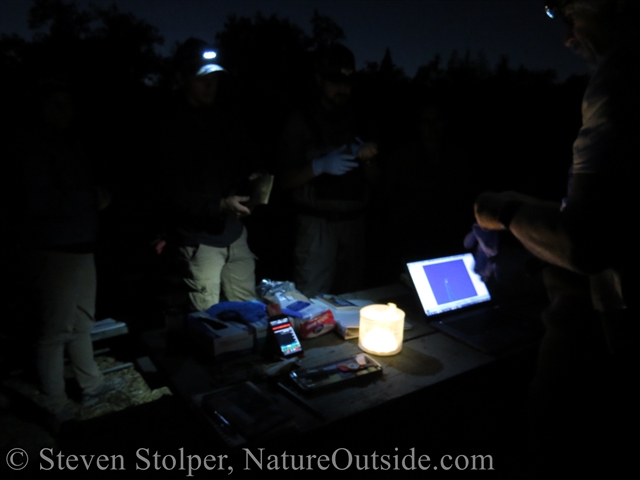

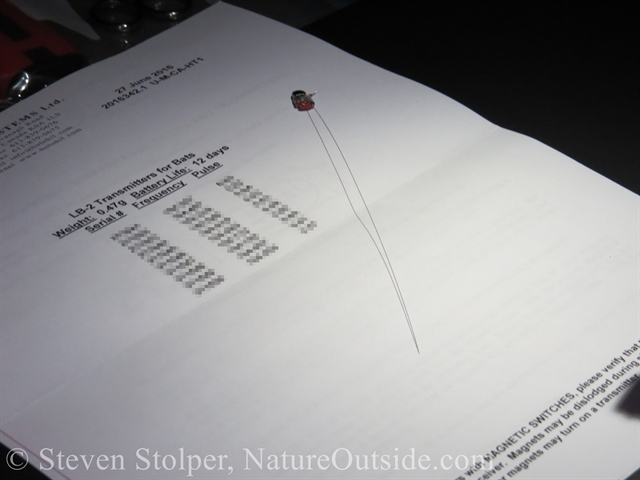

Each transmitter is smaller than a pinto bean. We test each one to make sure it’s working.

Bat transmitter, on paper for scale

Bat transmitter up close

Testing to make sure each transmitter is broadcasting

Batting By Ear

Some of the student have brought bat detectors. One of the detectors is new to me and very exciting.

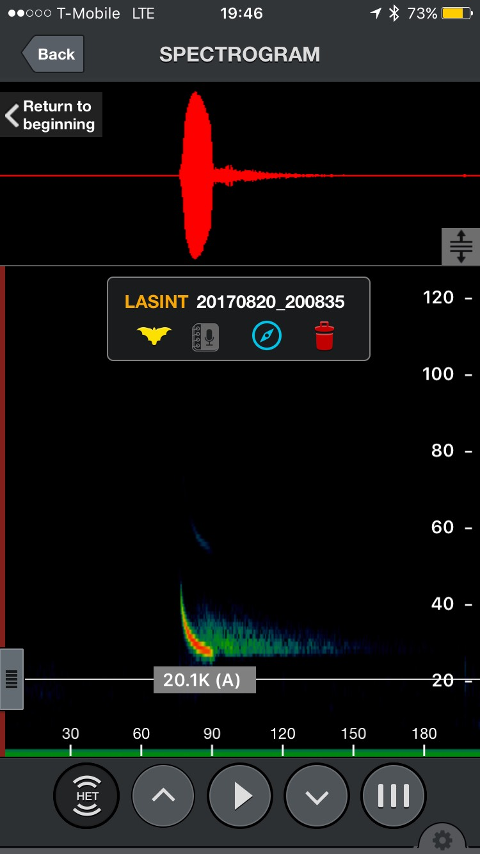

Natalie Downe is a chiropterophilia – a person who loves bats. She’s studied them for many years and her enthusiasm is contagious. Natalie has a device that’s new to me, an Echo Meter Touch 2. It’s an ultrasonic bat detector for your mobile phone!

The device plugs into the USB port of your IOS phone or tablet. And it will soon be available for Android devices. Not only does it detect bats, the Echo Meter Touch 2 identifies the species. There are thousands of bat species. And each has a unique call. The software running on the phone analyzes the incoming signal and classifies the bat accordingly. It’s very cool!

Natalie using Echo Meter bat detector

Echo Meter bat detector screen-shot

For more information on the device, you can visit the manufacturer’s website.

Another student, a professional naturalist, had an Anabat SD2. This is more of a field-hardened scientific tool, and is priced accordingly. Unlike the Echo Meter, the Anabat does not identify the bat for you. It captures the frequency of a call and leaves the analysis to the user.

Student using anabat

Checking the Nets

We deployed the nets just after 7:00 pm. We spent most of our time waiting at base camp, far enough away that we wouldn’t disturb the bats. After dark, we began checking the nets regularly. We didn’t want the bats to spend much time in the nets after they were captured. We didn’t want to stress them. But, more importantly, we didn’t want to risk the nets sagging into the water under the weight of the bats. The latter was a remote possibility because of how we pitched the nets. But we weren’t going to take any chances.

Checking the nets was an otherworldly experience. We hiked through the darkness to the waterside. It was nearly impossible to see the monofilament nets. Instead we looked for movement above the water.

There was a spooky aspect to checking the nets. The eyeshine from hundreds of tiny eyes shone from the far bank of the creek. It was the eyeshine of spiders caught in our flashlight beams.

Hiking to the creek

Hiking along the creek

Checking the nets

It’s nearly impossible to see the monofilament in the dark

Bad Luck

The sudden drop in temperature proved our undoing. We checked the nets approximately every 15 minutes until midnight. No luck!

Around 8:00 pm, our bat detectors lit up with calls from a Hoary Bat (Lasiurus cinereus). But these migratory bats forage high over open areas. We were unlikely to catch one down by the creek.

A Western Screech Owl took up residence nearby and started hooting down at us.

But no bats.

Worse Luck

Around midnight, Dave suggests we pack up the nets and head home. Sometimes nature is like that. You never know what you’re going to see. On those occasions when you see nothing, you need to take it in stride.

Dave reminds us that bats have a dual cycle. They feed after dusk and again before dawn. We agreed that Dave would put the nets back up at 4:00 AM. If he caught any bats, he would tag them and we would track them the following day.

When Dave contacted us the next morning, we learned that bad luck and turned to worse luck. Dave did not catch any bats. But he *did* encounter a family of skunks that took exception to his presence. They sprayed him! Ack!

To be Continued…

Dave felt bad that we weren’t able to catch any bats. So he said he would set up another outing when he returned from doing research in Hawaii.

Even though we didn’t catch bats, we still learned a lot. We set up and took down mist nets, used bat detectors, and learned many of the details of how to tag bats.

I look forward to our next outing…

References

(1) Bats – A World of Science and Mystery, M. Brock Fenton and Nancy B. Simmons

(2) Bat Squeaks Louder than a Rock Concert

Related Articles on NatureOutside

Stalking the Black Bear – High Adventure in the Forest (Part 1)

Owl Class – The Harry Potter School of Bushcraft

Wolves Teach a Master Class (Part 1)

For fun facts and useful tips, join the free Bushcraft Newsletter.

Leave a Comment